One of the biggest questions that new photographers ask when they’re purchasing a new camera is if they should spend the extra money and get a full-frame camera. It’s a reasonable question, especially when the vast majority of professional photographers are using full-frame cameras like the Nikon D850, Canon 5D Mk IV, and other similar cameras.

But that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a lot of value in using APS-C, or even Micro 4/3rds sensors. In fact, some of the fullest-featured cameras use these smaller sensors, and on many levels, they easily compete with top-of-the-line full-frame cameras. At least, if speed and video are necessary for your style of photography.

Smaller sensors offer incredible value. And for videography, or wildlife, sports, and other types of photography, they will perform far better than a full-frame camera in a similar price range. And, while landscape photography loves large sensors with incredible dynamic range and megapixels, the truth is it’s easy to get the same result using a smaller sensor.

Here’s an article I wrote earlier on getting professional results with an entry-level camera.

For now, if you’re looking to purchase your first camera, or upgrade to a new system, here’s my breakdown of each of the sensor size benefits and drawbacks.

The term crop factor gets thrown around a lot after this section, so this is the best place to discuss what that term means. If you already know what a crop factor is, then skip to the next section.

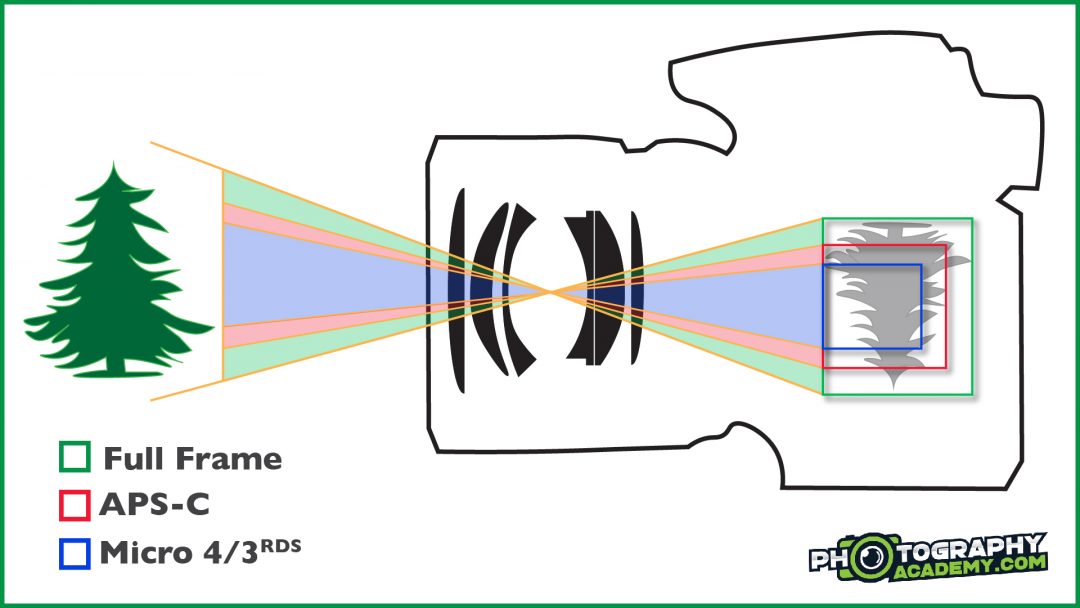

Crop factor is a term used to compare lenses between sensor sizes. Lens terms are standardized across formats, but they don’t respond the same way exactly. Focal length is calculated by how far away from the sensor the light converges, or flips. This calculation is the same no matter which lens format you’re using, but how much of the light is captured won’t be.

A smaller sensor will capture less field of view than a larger sensor. So a 24mm lens on an APS-C sensor with a 1.5x or 1.6x crop factor will have roughly the same field of view as a 35mm lens on a full-frame sensor. But on Micro 4/3rds, that same 24mm lens will look like 50mm on a full-frame body, because that sensor has a 2x crop factor.

The crop factor also applies to the aperture of a lens. So a 50mm lens with an f/1.8 aperture on a 1.5x APS-C camera will produce the same blur and depth of field as a 75mm lens with an f/2.7 aperture on full-frame.

If you have any questions about crop factor, feel free to leave them in the comments below.

A micro 4/3rds sensor is approximately half the size of a full-frame sensor. That means Micro 4/3rds sensors capture half as much light, produce more noise, and are only able to create half as much blur as a full-frame camera with an equivalent lens and aperture. Lenses are also cropped in 2x as much as they are on full-frame, meaning a 50mm lens on micro 4/3rds is equivalent to a 100mm lens on full-frame.

But, these sensors are much cheaper, and the cameras that use them are incredibly capable machines. Many manufacturers were able to overcome the limitations of small sensors by packing in features that were typically only found in top-of-the-line cameras. For example, there are sub-$1,000 Micro 4/3rds cameras able to shoot 4K video with stabilized sensors, that have incredibly large megapixel counts for their size.

As well, the Micro 4/3rds system has a universal lens mount. Meaning lenses made by one manufacturer can fit on any Micro 4/3rds camera. That extra competition opens up plenty of high-quality glass at lower prices.

A perfect example is the Panasonic DC-G9. This camera regularly goes on sale below $1,000, yet it can shoot 4k60, has dual card slots, weather sealing, a stabilized sensor, an incredible 60fps photo burst mode, a touch screen, and a high-resolution pixel shift mode that can produce 80-megapixel images on a tripod. This cheap camera has better specifications than cameras that are 2x or even 3x more expensive.

The biggest reason why photographers don’t all flock to Micro 4/3rds, however, is because of the noise and decreased dynamic range compared to full-frame. When shooting in low light, the image noise can ruin what would otherwise be fantastic photographs. The lower dynamic range also means that there aren’t as many details in the highlights and shadows of an image, reducing the photographer’s ability to edit photographs.

When shooting landscape photos, however, the limited dynamic range isn’t a big deal with modern photo processing. Simply create an HDR image to get even more dynamic range than full-frame cameras.

With a bit of knowledge and expertise, Micro 4/3rds is an excellent system for anyone who doesn’t need extreme low-light performance. Because cameras with this sensor size are packed to the brim with professional features, Micro 4/3rds cameras can provide incredible value for new or existing photographers.

Great for: Landscapes (with HDR and Panoramas), video, outdoor sports, wildlife, and adventure photography

Not so great: Astrophotography, portraits, low-light events, products, or concerts.

APS-C is the middle of the road sensor size. These sensors are larger than micro 4/3rds, but smaller than full-frame. Canon’s APS-C sensors have a 1.6x crop factor, while Sony, Nikon, and Fuji use a slightly larger sensor with a 1.5x crop factor.

These cameras have much better low-light noise performance and significantly better dynamic range than Micro 4/3rds cameras. But because they’re typically prosumer or entry-level cameras, they don’t pack in as many features as the micro 4/3rds manufacturers. For wildlife and landscape photographers, though, these cameras still retain their value.

For wildlife photographers, in particular, this crop can make a big difference in their photographs. The smaller sensor means that every lens reaches further on an APS-C camera than it will on full-frame. As an example, a 400mm lens will become 600mm on a 1.5x crop APS-C camera. And, because the APS-C camera has more megapixels in a smaller area, the images will actually be sharper than a full-frame camera cropping to the same 600mm.

Higher-end APS-C cameras follow the same principles as micro 4/3rds, where they typically have the same specs as top-of-the-line full-frame cameras, but at half the cost. For example, the Canon 90D, released in 2020 has a 32.5-megapixel sensor, shoots 10fps as well as 4k30 all for just $1,200. These specs aren’t found in a full-frame camera until you get to the $2,500 5DmkIV, which has fewer megapixels and can only shoot 7fps.

But in general, Canon, Sony, and Nikon have really only just started to pay attention to what modern consumers need in their cameras. For the longest time, these cameras were just paired down cameras that make the full-frame versions look good. So many APS-C DSLR cameras on the market (minus Canon’s 90D) are notably behind in video specifications. Mirrorless varieties like Sony’s a6000 series (find the latest ones on B&H here) fill in this gap for prosumers. But they’re still not as video feature-rich as the Micro 4/3rds cameras.

Great for: Sports, action, wildlife, and landscapes.

Good for: Low light, portraits, events, indoor sports, video, and product photography.

Not so great: Astrophotography, professional low-light events like weddings.

The reason professionals pay twice as much for full-frame comes down to a couple of factors. The biggest reason portrait photographers love full frame is that it allows them to get blurrier backgrounds, separating their subject from the background. But photographers shooting landscapes and other forms, love full-frame for a number of other benefits they provide.

The most obvious benefit is better low-light ISO performance. Because of the larger pixel-to-body ratio of the sensor, the camera will be able to capture more light, which results in cleaner, more detailed images.

The last reason, and likely the most important one for wildlife photographers is dynamic range. Dynamic range is the amount of detail that a camera can record in the highlights and the shadows of an image.

A camera that has a more dynamic range will capture more detail and will be able to recover highlights and shadows in Lightroom and Photoshop to a greater degree than a camera with a lower dynamic range.

This extra dynamic range helps landscape and portrait photographers capture all of the details in a scene without blowing out the details in the sky, or creating muddy, noisy shadows. At sunset and sunrise, this is especially important, because the scenes can be so contrasty that it’s impossible to capture all the detail in a single shot — especially with the smaller sensors.

The downside of full-frame cameras is the investment needed to get a camera that shoots 4K. Modern mirrorless cameras are bridging this gap, but for the longest time, Canon and Nikon refused to add anything but basic 4K specifications into their $3,000+ DSLR cameras. However, they seem to be keen on adding this functionality now that Sony took a large portion of their market share by offering these specifications on more affordable cameras.

Good for: Nearly everything.

Not so good for: Video on a budget.

The best deal on the market right now is the Nikon D850. This full-frame DSLR camera is still one of the best digital cameras ever made. Even though it was made in 2017, the Nikon D850 still has one of the best sensors ever made, and it is full of functionality that every professional photographer needs.

The camera comes with multiple memory card slots, long better life, high burst rates, and features a best-in-class 45-megapixel sensor with a class-leading 14.8EV dynamic range. Find the Nikon D850 on B&H, where you’ll get this camera for an incredible discount.

I’ve been using the Nikon D850 since it came out, and it has made a big difference in my photography. Find my full review of the Nikon D850 camera here.

There’s a point in every photographer’s career where they start looking into whether or not they need a medium format camera. These cameras are known for their extremely high image quality due to having larger sensors that capture more light than traditional full-frame. The same principles that exist for film exist in digital photography, where shooting a larger film format allows the user to get a similar image with much less grain.

But for the vast majority of photographers, the answer is no, you don’t need to drop $20,000+ on a medium format camera rig. Right now, these cameras are only useful for photographers shooting landscapes, high-end fashion/portraiture, and product photography. While these cameras may be prized in those fields, they’re still not absolutely necessary. The sensors may be able to capture more details in the highlights and shadows, as well as taking images with less noise than digital cameras. But their lens selection is still much smaller, and not necessarily sharper than most full-frame lens manufacturers.

The other problem is that these cameras shoot painfully slow. Look at the reviews around the Hasselblad and Fuji medium format cameras, and there’s a trend towards shooting no more than 3fps and having frustratingly unreliable autofocus. In the future, these trends may change. Particularly so if Canon, Nikon, or Sony join in on the medium-format photography game. But at this point, there’s no reason to spend that kind of money on a camera when there are full-featured cameras with never-before-seen specifications at half the cost.

Good for: Multimillion-dollar companies needing the highest resolution and image quality possible, or doctors, lawyers, and engineers with a photography hobby

Not so good for: anything else — yet.

Once you’ve made a choice about a camera, the next step is to continue learning about photography! The camera is only one small part of the equation, but the photographer is what really makes the photograph. I have created a simple, four-step system of photography that will teach you how to take your photos to the next level using the camera that you already have. It all comes down to planning, composing, and painting the images with light. Once you see the process in action, you’ll be amazed by how simple it is to add into your workflow. Learn more about it today by signing up for the free online web class!

Once you’ve made a choice about a camera, the next step is to continue learning about photography! The camera is only one small part of the equation, but the photographer is what really makes the photograph. I have created a simple, four-step system of photography that will teach you how to take your photos to the next level using the camera that you already have. It all comes down to planning, composing, and painting the images with light. Once you see the process in action, you’ll be amazed by how simple it is to add into your workflow. Learn more about it today by signing up for the free online web class!